Bolivia

We’ve experienced Bolivia as an unusual place. A land of extremes. It felt raw. Situated on top of the mountains, almost touching the clouds, it hosts some of the highest settlements on earth. On 4000-5000m altitude the air is thin and dry, the sun and wind unforgiving.

The landscapes are breath-taking. An array of surreal backdrops with multicoloured mountains, lagoons, and dramatic cloud formations… Many times we felt like traveling inside a painting.

Not much grows on this altitude, but the land is dotted with wildlife. Vicuñas, llamas and flamingos survive even the harshest climates.

Bolivia is beautiful and surprising. People seemed reserved with a strong sense of pride. As foreigners we weren’t always welcomed with a smile, but the authenticity made up for the lack of it.

We’ve certainly had the most unfriendly border crossing on this journey. The resentment in particular of the U.S. is palpable and expresses itself not only in a steep 160USD visa fee. Foreigners are not allowed to buy gasoline or diesel at most gas stations. Only a few are permitted to sell it at a much higher rate with a special receipt. This is because the gasoline for Bolivians is highly subsidized by the state, and they naturally don’t want to extend the same privileges to foreigners. This makes traveling overland difficult and a bit of a guessing game.

Despite these obstacles, Bolivia offers impressive experiences, with some of the most stunning landscapes we’ve ever seen.

We entered the country at Copacabana, a town located on the shores of lake Titicaca. There is no land connection to the rest of Bolivia, so we had to put our truck on one of the dilapidated little ferries to cross.

Once back on land, we started heading towards the capital, La Paz.

Eager to experience the fueling challenge first hand, we tried to fill our jerry-cans at a gas station. “No permitido” is what we were told. But some houses had signs reading “Se vende gasolina”. So we knocked on a few doors until we found one that filled our canisters. It’s strange, not being permitted to buy such fundamental things with ease… Makes you question what is a right and what is a privilege.

La Paz is the highest capital in the world and one can easily feel the shortage of atmosphere walking in its streets. For us, the city meant a little more than hunting for vehicle insurance.

A police officer at the border had tried to get a bribe from us for not having insurance even though there’s no way to buy it there and it’s not obligatory to carry it. But we still wanted to take care of it in the capital because we could buy coverage for Argentina and Chile with the same policy, which will save some further trouble.

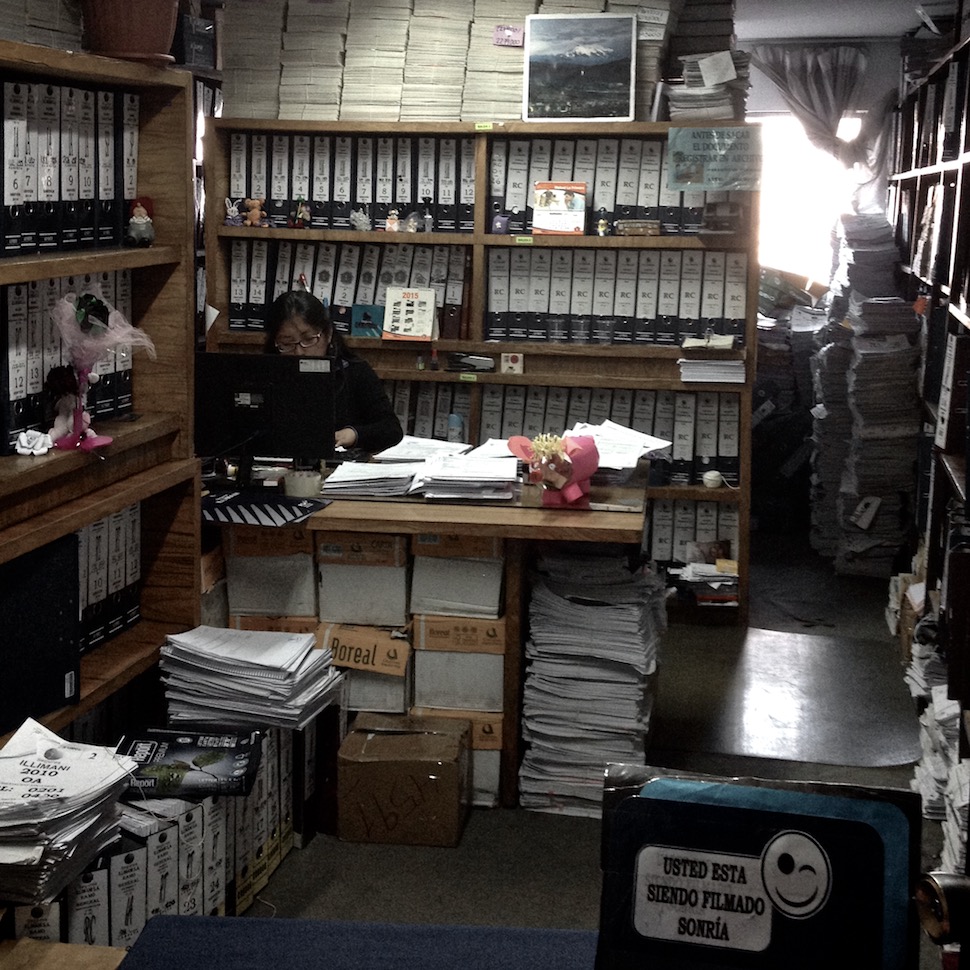

The office was a curious place straight out of a dystopian movie where the characters are working inside a tall building in the highest capital of the world but buried under stacks of paper. Felt like fiction, but was real…

We met Michael & Claire and their three kids in La Paz. They were planning to do the same route so we decided to travel together for a while. We did not know at that point, that this was going to be the first meeting of a convoy of six vehicles!

A storm found us on the way to Potosi and the sky turned dark. It felt like we could almost touch the darkness looming above us. The cloudscapes over the Bolivian altiplano were just incredible. Awe-inspired and slightly threatened, we traveled on in our faraday cage, hastily zipping over the wide open highlands in seek of shelter.

We camped somewhere along the road as the sun was setting, making way for a bitter cold night. The storm moved on, leaving us with a huge starry sky above.

This curious man appeared out of nowhere and greeted us in the morning. His eyes and mouth seemed to be hidden deep inside his head and he spoke softly and gently in words hard to understand.

Life in Bolivia seemed largely rural and basic. Small adobe farm houses, and ox ploughing the fields, marked the landscape. Time seemed to stand still. We felt a bit like aliens on a foreign planet.

In Potosi we had to take care of some simple paperwork to travel to the next country with our dog Tara, while Michael and Clair’s family tried to find a camp spot for the night. Since they had trouble entering the narrow roads of Potosi with their big rig, they decided to continue on, and we joined them later in Uyuni.

Potosi is known for it’s silver mining. It is one of the highest cities in the world, on 4,090 metres (13,420 ft). Simply walking along the streets feels like hard “work” to us with the little oxygen at this altitude. It is hard to imagine working inside a mine under the most strenuous and dangerous conditions.

We were curious about the famous mines, and booked a tour with one of the many companies in the town. We specifically picked one that gives a higher percentage of the fee to the mine workers, which provides some support to their livelihood.

The first step of the tour was the Miners’ Market. This is probably one of the rare places in the world you can walk into a corner shop and walk out with a bundle of dynamite under your arm. No questions asked! If you want you can also add some nitroglycerin capsules and ammonium nitrate to add flavor to the intended explosion. In addition to the lack of control, it’s also possible to find all kinds of mind altering substances including pure drinking alcohol and coca leaves. No one really oversees what’s being used or consumed in the mines. Here, everything is ‘at your own risk’! And understandably so…

It is common to buy gifts for the workers when going to the mines. They have to buy all the material by themselves and a little support for the privilege of visiting is welcomed. The work in the mines is exhausting and dangerous. In order to cope with lack of oxygen and suppress hunger, large amounts of coca leaves are consumed. Bicarbonate and other salty or sweet mixtures are also used to activate the plant’s chemicals.

The silver mines of Cerro Rico in Potosi, literally lie at the heart of Bolivia. The mountain provides a large part of the countries income. Historically speaking, it has also served the interest of the Spanish Empire. It has been claimed that with the amount of silver excavated here, it would be possible to build a bridge connecting Potosi to Spain. And another one with the bones of the workers who died in the mines… The average lifespan of a mine worker is 40 years. That is to say, you die within 15-20 years of your employment.

The mountain is being excavated by many different cooperatives and several hundred people work on it each day. With the excavations going on since the 16th century, the mountain started sinking and had to be filled in on certain parts to avoid a catastrophic collapse. One needs to make a pact with the devil to enter here every day to work. And they do.

Tio, the God of the miners, was originally introduced by the Spaniards who wanted to intimidate the indigenous workers with the idea of a devil. However, the figure was quickly integrated and adapted into the spiritual subculture. Now the workers bring offerings of coca leaves, cigarettes, and alcohol to their protector, all the while celebrating along side him of course.

Every cooperative has their own Tio alter. It would be interesting to know how many of these figures are hidden inside the mountain by now.

This worker suddenly came out of a small hole, starting to pull down gravel into a cart. Despite the strenuous work, the miners seem to have a sense of humor and lightheartedness to them.

Sarah is reluctantly helping a miner to prepare dynamite and ammonium nitrate sticks, which the workers confidently pounded on a box of fragile nitro-glycerin capsules to consolidate the content. No wonder the mountain has swallowed so many worker’s lives over the decades.

The mountain Cerro Rico is carved at the center of Bolivian coins. The miners in Potosi see themselves as the driving force of the Bolivian economy. There are many protests against president Evo Morales, who they feel takes away their profit without investing into the city in return. Once perceived as the countries humble son, Morales seems to have lost his popularity amongst the workers we’ve talked to.

The dynamite sticks are cut into three pieces and fittet with a nitro-glycerin headed fuse. While inside the mine we heard several explosions in the distance. It’s an uncanny experience to be inside a mountain that has more holes than a piece of cheese, and is being worked on by hundreds of miners every day.

A piece of silver. Tons of material have to be transported outside the mine everyday, to extract some of the valuable metal in refineries.

These heavy carts are pushed by hand. It is an incredible weight to move all while crouching through the low and narrow tunnels.

After two hours in the mine, we were tired. Incredible what the workers can accomplish performing such challenging labour in the dark all day without eating.

Washing up the borrowed boots at the exit.

Our 60D with the wide lens served well and survived the mud.

Saltenas are basically empenadas filled with all kinds of yummy juicy ingredients. It’s the best food you can have with dirty hands in a dusty environment.

After negotiating with a gas station attendant to fill our gas tank and jerry cans in Potosi, we headed on to the dusty town of Uyuni on the edge of the salt flats.

Llamas walking alongside the road during sunset. We’ve seen so many of these Andean camelids by now, but they still put a big smile onto our faces each time.

In Uyuni we were reunited with the Swiss family of Claire and Michael and the French couple Sidonie and Vincent whom we’d met in Potosi. We arranged to all travel together through the barren sections of the Salar the Uyuni (the biggest salt flats in the world) and the Laguna Route.

This undertaking meant more than a week off the grid, on high altitude dirt roads, freezing temperatures, without any gas stations, water, showers, and barely any signs of civilization. This would probably be the roughest stretch of land we’d travel through. We had heard different accounts of how long the road really was and how many days it would take. We didn’t quite know how much gas we would need to carry or how much food and water to bring. We all stocked up as good as possible, but were glad to have the comfort of company on the rough roads ahead…

An old train graveyard provided our last camp before heading out to the Salar.

A lonely young vicuña in the middle of the desert. They sometimes wander too far off into uninhabitable landscapes. We hope this one finds its way back to the herd.

The famous Salt Flats of Uyuni. Probably one of the weirdest places to drive a vehicle on. There was no water on the surface when we were there at the end of October. The route is clearly visible and distances are manageable. In fact, this was probably the best ‘road’ in Bolivia.

With such different vehicles, we appeared to be a perfect match for a tough expedition. Vincent and Sidonie will compete in the “Cute Van” category while Michael and Claire will challenge the RV category of the 2016 Dakar.

The whiteness of the Salar provides a blank canvas and inspiration to play. We all took our turns to do the traditional Salar compositions after the lunch break. Silly as they are, these photos are not always easy to take.

The most beautiful creations by far were done by mother earth. The sunset over the salar, adding a subtle glow to the cacti towering over Isla Incahuasi, was stunning.

The breakfast before departure. Sarah here is cooking “high on salt”.

Chinchilla-like rodents were hopping around the island. It’s hard not to wonder how they got here in the first place. The image of an over-ambitios pregnant rodent hopping over an infinite white surface for days, is a bit far fetched. They were probably brought here by over ambitious people.

The white salt combined with the freezing temperatures and wind, made it hard to not think of it as snow, so we decided to make a salt-man instead of a snow-man. Upon a brief discussion about subconscious sexism, we decided to call this a salt-woman and name it Sally!

We spend two nights in the Salar before continuing on South into even rougher terrains. We will always remember our moments on this huge nothingness.

The only settlements we encountered on our way to Chile were two tiny towns, which offered a few provisions and a couple of litres of gasoline. We bought 15 litres, which turned out to be a bad decision. There were two white blobs of who-knows-what in the canister and now in our tank. There was nothing to do so we drove on hoping that we wouldn’t end up with a clogged fuel system. Luckily, all we got was a fuel injector sensor warning after a few weeks of driving, which was cleared up by an injector cleaning session in an Argentinian mechanic shop.

One of the towns was next to an ancient necropolis, with mummies encased by rock mounds.

In the small town of Alota we decided to split into two groups. There is an easier and a harder stretch of the laguna route, and only the two 4WD’s including ourselves were willing or able to tackle the more challenging road. So we took off into the mountains with Urs and Barbara.

We passed incredible landscapes, lagoons dotted with flamingos, kilometres of washboard, sandy roads, rocky patches, harsh winds and lots of camelid carcasses (which Tara was happy about).

The altitude made it hard to breathe at night, and the wind almost impossible to cook outside. It was comforting and pleasant to travel with the seasoned Swiss couple who have been traveling on a well prepped Land Cruiser. We admired their compact and easy set-up (Tom’s Worldcruiser) very much.

A hidden little lagoon provided some wind shelter for the night while we watched a group of flamingos get trapped in the frozen lagoon.

Sun, wind, and dust quickly changed the color of our skin and cracked our lips. After a couple of days on this high altitude route, we started to look like we had been on the road for years… Well, in a way, we are.

Arbol de Pietra in a sand storm. There was so much wind we could barely walk and the sand was hitting our bodies like tiny bullets. Photographs often manage to beautify moments, and make memories of nearly unbearable weather conditions quickly fade away. These rocks have been shaped by time and likely many many more sand storms.

The Laguna Colorada was our meeting point with the other group after one night and two days on different routes. Some of these landscapes made us feel like we’d landed on Mars.

The winds were so harsh this day that it was uncomfortable to walk outside. After looking for the other group for a while, we finally spotted them on the opposite side of the gigantic lagoon.

We quickly carried on to a canyon which provided at least a little bit of wind protection. The nights at this altitude are far below freezing. Waking up with -6°C inside the vehicle, makes it hard to get out of the sleeping bag. Ordinary tasks like washing the dishes become a challenge, when the water is freezing as you’re trying to rinse off the soap.

The next day we slowly made our way up to the aduana (customs) office at 5033 meters. We had to stamp out our vehicle papers in a settlement before hitting the actual border for immigration two days later in another one. A peculiar detail you don’t want to miss if you like keeping your papers in order.

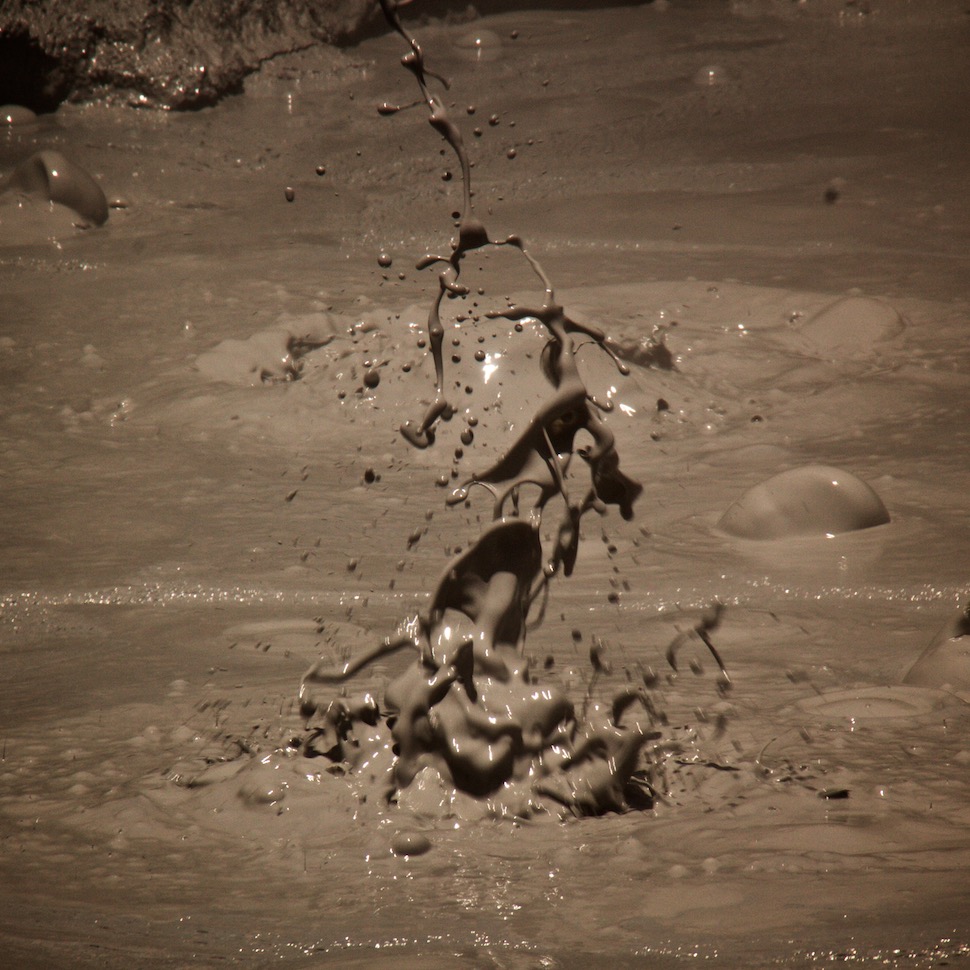

There are several geysers in this volcanic area. With all the geologic activity in the absence of vegetation, it feels like the earth is alive and moving.

There is a small thermal spring at the shores of one of the lagoons. It’s frequented by many tourists on private tours but we had it all to ourselves. Soaking our bones in hot water was a great delight after almost a week in the freezing cold and without showers.

The Dali Desert is indeed a surreal place to be in. The rocky blocks protruding the sand makes it look like someone placed them there with purely aesthetic intentions.

We over-calculated our fuel needs. Other travelers told us we had to prepare for 900km without gas stations so we carried an extra 120L in six containers bringing our capacity up to 220L (including the extra 20L we carry on the bumper swing-arm). The route was closer to 560km without fuel points and we would have been fine with 80-100L because we did not use the 4WD too much. This is all calculated on a 3.4 V6 Toyota Gasoline motor. They usually come with 80L tanks so if you want to do the Laguna Route on a similar vehicle, just get one or two 20L cans to be safe and don’t worry about it as much as we did.

A fox greeted us at the Chile/Argentina intersection right after passing the Bolivian border. Coming down to only slightly above 2000m was wonderful. The temperatures rose with each meter of decent and by the time we reached San Pedro de Atacama our clothes had to come off…

Meeting other travellers in this remote region was so inspiring, we pulled out the video camera a bit more often than usual, and prepared a short film to make the experiences we had together more memorable for all of us.

Sidonie, Vincent, Claire, Michael, Soraya, Jimmy, Amelie, Barbara, the other Barbara, Urs, Mark, Remo, Sylvia, Shannon, Mike… It was a great pleasure to get to know you. We all had the perfect timing!

1 Comment

francesco

November 9, 2015absolutely wonderful. so glad that you are sharing this with us! love to you sarah.